Contents

One of the 21st century’s leading causes of disability is mental illness. According to a study published in The Lancet Global Health journal in 2020, mental illness affects an estimated billion people worldwide. Depression is the number one contributor to the list of mental illnesses. It is showed that more than 250 million people have been suffering from this condition globally. The first-line treatment for this condition is antidepressant medications. According to Public Health England, the number of people prescribed antidepressant medications is increasing each year, making this market valued at approximately $15bn.

Since accurate record-keeping began, depression prevalence rates have not decreased. Psychiatry has long failed to explain depression. Another reason for this paradox is the failure of science to explain the mechanism of depression adequately.

Medication for Depression according to modern psychiatry

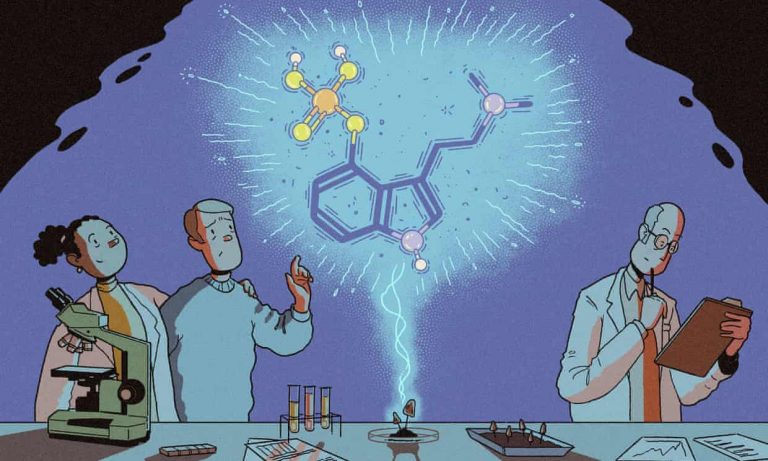

Modern psychiatry has long been unable to find a convincing biomedical explanation for depression. The Serotonin Hypothesis is one of the most accepted concepts, which was inspired by the observation that drugs increase the activity of this naturally occurring brain chemical that has antidepressant effects. Prozac, chemically known as fluoxetine, first produced in the mid-1980s, is the most popular Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant. Currently, Cipralex (escitalopram) is one of the newest and best performing.

This hypothesis suggests that people are depressed because their serotonin levels are too low, which is not always the case. Though the Serotonin Hypothesis has some scientific foundation, it has been massively oversold, and some serious side effects have been observed over time. The latest scientific evidence demonstrated that SSRIs like escitalopram are only marginally more effective as a treatment for depression than a placebo. And these response rates tending to average around 50%-60%. On the other hand, there are some limitations too; for example, SSRIs include poor accuracy with which a patient follows an agreed treatment, some unavoidable symptoms when people stop the medication, unpleasant side-effects, and the sluggishness of antidepressant effects.

Psychiatric Medication vs. Psychedelics for depression

The current head of the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, Robin Carhart-Harris, 15 years ago, as part of his Ph.D., started to begin investigating an alternative to antidepressant medicines. Among all other alternatives, the classic Psychedelic substances showed highest potential. Psilocybin is an active Psychedelic compound of Magic Mushroom. When consumed in high doses, it profoundly alters the quality of an individual’s conscious awareness while producing complex visions with insights and brings out suppressed memories and feelings.

After completing a series of research involving Psilocybin, including earlier trials of effects among people suffering from treatment-resistant depression, Dr. Carhart-Harris designed more rigorous test methods based on the previous study result. This time the main goal was to help to contextualize Psilocybin’s therapeutic promises. The resulting trial was completed last year, and the findings of that study have been published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

It was a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial with the participation of 59 people who were suffering from moderate to severe depression. They were randomly allocated into two treatment groups: one in which the main treatment was a six-week course of the conventional SSRI antidepressant, escitalopram, and another in which the main treatment was two high-dose Psilocybin therapy sessions.

Those in the escitalopram group did about as well as one would expect, based on previous SSRI trial data and the relatively short, six-week course. Across four different measures of depressive symptoms, the average response rate to escitalopram at the end of the trial was 33%. In comparison, Psilocybin worked more rapidly, decreasing depression scores as early as one day after the first dosing session. At the end of the trial, the average response rate to Psilocybin therapy was more than 70%.

From the beginning, the researchers suspected that Psilocybin might perform well compared to the pharmaceutical SSRI, but the result was astonishing. The initial hypothesis for this trial was that the Psilocybin therapy would have superior effects on overall psychological wellbeing but not on depression severity scores. This prediction was generally supported, but people in the Psilocybin group also demonstrated evidence of greater improvements across most depression measures, anxiety symptoms, work, social functioning, suicidal feelings, and the ability to feel emotion and pleasure.

Both groups experienced similar levels of side effects, but the escitalopram group experienced worse drowsiness, dry mouth, sexual dysfunction, and anxiety. On the other hand, in the Psilocybin group, the most prevalent side-effect was a mild to moderate headache one day after dosing. Six-month follow-up work is currently underway to test the second prediction that the positive effects seen in the Psilocybin group will be long-lasting.

Why does Psilocybin appear to be a more successful alternative treatment for depression than a typical antidepressant?

Brain imaging data from the trial, alongside the psychological data researchers collected, demonstrated that while SSRIs dampen emotional depth by reducing the responsiveness of the brain’s stress circuitry, assisting in taking the edge off depressive symptoms, Psilocybin seems to liberate thoughts and feelings. By dysregulating the neocortex, it accomplished this. The neocortex is the most evolutionarily developed aspect of the human brain. When this liberation occurs, new possibilities open up too to perceive things in a new light; in this state alongside this with professional psychological support there can be a renewed breadth of perspective. Psychedelic therapy seems to catalyze a type of psychological growth that is conducive to mental health, and overlaps, in many respects, with spiritual growth.

According to the authors of the study, the most exciting aspect of this trial is the sense that we are on the verge of a paradigm shift in mental healthcare connected to an improved understanding of the origins of depression. Now we understand how we can most effectively treat depression with proven results.

According to Carhart-Harris, this shift will take us away from an outdated “drug-alone” perspective which has dominated psychiatry for several decades. This shift is towards a multi-level “biopsychosocial” model-(an interdisciplinary model which looks at the interconnection between biology, psychology, and socio-environmental factors). This model sees the symptoms of depression as an adaptive response to adversity, with decipherable, complex, psychosocial causes.

Psychedelics can treat depression by activating powerful brain states which have evolved in humans to catalyze deep psychological change. When these “hyper-plastic” states are combined with a nurturing environmental context, defensive habits of mind and behavior can undergo a healthy, potentially enduring revision.

Conclusion

As a limitation, the authors also mentioned that the outcomes of the study generally favored Psilocybin over escitalopram, but the analyses of these outcomes lacked correction for multiple comparisons. Larger and longer trials are required to compare Psilocybin with established antidepressants.

The authors also cautioned that the result of this study certainly could not be used as a license for people to self-medicate. According to the authors, these are exciting developments which are acknowledged by the different government bodies, with the U.S. state of Oregon having already voted in favor of legalizing Psilocybin therapy; also, a senate bill having been passed to decriminalize Psychedelics in California with policies which are being reviewed in Washington DC, New York, Florida, New Jersey, Canada, Australia, and the UK.

References

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Nutt, D. J. (2017). Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), [online] Volume, 31(9), p. 1091–1120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117725915 [Accessed 10th August 2021].

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Rucker, J., Day, C. M., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., Bloomfield, M., Rickard, J. A., Forbes, B., Feilding, A., Taylor, D., Pilling, S., Curran, V. H., & Nutt, D. J. (2016). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. The lancet. Psychiatry, [online] Volume, 3(7), p. 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7 [Accessed 10th August 2021].

- GOV.UK. (2020). Prescribed medicines review: summary. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prescribed-medicines-review-report/prescribed-medicines-review-summary [Accessed 10th August 2021].

- Hirschfeld R. M. (1999). Efficacy of SSRIs and newer antidepressants in severe depression: comparison with TCAs. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, [online] Volume, 60(5), p. 326–335. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v60n0511 [Accessed 10th August 2021].

- The Lancet Global Health. (2020). Mental health matters. The Lancet Global Health, [online] Volume 8(11), Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30432-0 [Accessed 10th August 2021].