Contents

Everything about Plants is balanced. A full-grown Plant is a symbol of balance. From root to shoot, in various phases, a Plant has to actively balance many elements. Balancing and symbiosis comes hand in hand, which Plants have mastered over many millions of years.

Plants are constantly exposed to microbes: commensals which cause no harm or benefit, pathogens which cause disease, and symbionts which promotes Plant growth or helps fend off harmful pathogens – Plants balance them both at the same time, an act which has been puzzling the scientific world for many years.

For example, most land Plants form mutualistic relationships with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi to improve water and nutrient uptake. How Plants fight off pathogens without wasting energy on commensal microbes or killing beneficial microbes is a mystery and a largely unanswered question.

In fact, when experts within the field of molecular Plant-microbe interactions were asked to list their top 10 unanswered questions, the number one question was “How do Plants engage with mutualistic beneficial microorganisms while at the same time restricting harmful pathogens?”

Expert discussions and debates on the question

As part of a Top10 Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions (MPMI) review series in the open-access MPMI Journal, this question of how Plants and microbes engage in symbiosis was recently interrogated by Dr. David Thoms and Dr. Cara Haney, microbiologists at the University of British Columbia, in collaboration with Dr. Yan Liang at Zhejiang University in China.

Dr. Haney emphasized that maintaining a balance in Plant disease resistance where Plants can fight off pests and other harmful pathogens but at the same time still can engage with microbes which can assist in water and nutrient uptake is crucial for the health of crops. He further reminded that to fully engage with such a large question, specific paradigms are needed to drive specific research questions towards the unanswered question.

According to Haney, this question is so broad that the current review raises more questions than it answers. The research team attempted to highlight much of what was already known, but also what the scientific world still does not know, to give paradigms and models that could be used as frameworks going forward.

How Plants balance microbial friends and foes

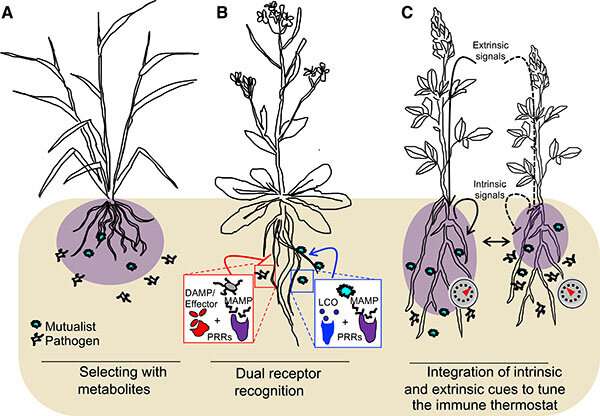

Considering mechanisms of symbiotic relationships, in a proposed framework, Haney, Liang, and Thoms distinguish three principles:

- Chemical selection with metabolites

- Dual receptor recognition

- An immune thermostat.

Plants first use metabolite compounds like chemical signals and antimicrobials to recruit beneficial organisms and restrict pathogens, but not all pathogens are excluded in this step. Thoms proposes that once Plant and microbes are in contact, “a dual input model” is used by the Plant to identify both the type of microbe (Fungal, bacterial, or nematode) and their lifestyle (commensal, mutualist, or pathogen). Thoms further explains that Microbes can be detected by receptor proteins on the surface of Plant cells. When receptor proteins detect a Fungal cell wall known as chitin, the Plant identifies a Fungal microbe presence. But as chitin and other microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPS) are often shared among microbes, they are insufficient signals to distinguish commensals from pathogens.

According to experts, unlike most animals, Plants do not have an adaptive immune system. But Plant genomes carry many more innate immune receptors than animals. Dr. Liang explains that Plants also use similar receptors to sense signaling molecules from beneficial microbes, environments, as well as their own cells. So, additional receptors use a second layer of information to identify pathogens versus mutualists. Symbiosis receptors can identify signaling molecules specifically produced by beneficial microbes, while immune receptors can identify pathogen proteins intended to shut down Plant defense.

Addressing how do Plants know both the type and lifestyle of a microbe, Thoms remarks, it is remarkable that Plants can perceive so many types of microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPS) across different kingdoms of life, and one use of that is recognizing where the microbe is coming from to provide the appropriate physiological response. In other words, a Plant cell actually follows a flowchart to determine what reaction is needed in response to the type and lifestyle of the microbe it recognizes.

Yet, a Plant can simultaneously engage with multiple microbes which require different responses, making it more complicated than following the flowchart directly. Plants have to balance the energy use for immunity and symbiosis based on present microbes and current Plant needs. So, how do they do this? The answer is “normal immune setpoint”.

Haney explains that it is important to realize what this is and how it can be adjusted over a Plant’s life to maximize crop yields. Because of the influence of the environment and nutrient stress as well, how Plants decide to use resources to interlock in symbiosis or prevent disease is perhaps one of the biggest areas for exploration.

The research findings strongly suggest that in order to obtain a healthy balance between Plant growth and Plant defense and maintain microbe-Plant homeostasis, the Plant root microbiota needs to include both immune-suppressive and non-suppressive bacterial strains in balanced proportions. Having too many or not enough of either type of bacteria in the Plant microbiota could be detrimental to Plants, as it could result in increased disease susceptibility and poor Plant growth. According to the lead author Ka-Wai Ma, Plants are known to have an intimate association with their microbiota; surprisingly, the scientific world still does not fully understand their influence on the Plant immune system. This study serves as a good example of how a balanced microbiota is important to modulate Plant traits of interest. From a translational perspective, these findings have potential if one can manipulate the microbiota in such a way to tip the balance for the benefit of the Plants.

Conclusion

According to Haney, the problem of identifying and responding to different microbes in variable environments is not only unique to Plants, but also in many living organisms, ranging from Plants to humans, who are faced with the challenge of engaging with beneficial microbes while restricting harmful pathogens.

Understanding Plant-microbe interactions may shed light on eukaryotic interactions with microbes in diverse organisms.

References

- Ma, KW., Niu, Y., Jia, Y., et al. (2021). Coordination of microbe-host homeostasis by crosstalk with Plant innate immunity. Nature Plants, [online] Volume, 7, p. 814–825. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-021-00920-2 [Accessed 22nd September 2021].